In the previous post, we explored how measuring current after stepping or during sweeping, through techniques like chronoamperometry and voltammetry, can offer insight into electrochemical phenomena. In this chapter, we swap things around: what if we control the current and instead observe how the voltage responds?

This is the core idea behind chronopotentiometry and related galvanostatic techniques. Rather than observing how current reacts to a voltage step or sweep, we apply a fixed current and watch how the system adjusts its potential in reaction to the applied electron flow. The resulting voltage-time profile reveals again a great deal about the thermodynamics, kinetics, and transport limitations of the system.

We explained previously that potential can be thought of as a metric to determine whether an electrochemical reaction would occur spontaneously or not. The potential of an electrode is always expressed relative to a well-defined reference electrode – by definition versus the standard hydrogen electrode which has 0 V. Voltage, on the other hand, is the measurable difference in potential between two electrodes. Voltage determines the direction and extent of electron flow between these two electrodes. So, potential is for one electrode, whilst voltage always involves two electrodes.

In chronopotentiometry, a constant current is applied to an electrochemical system, and the resulting voltage is recorded over time and plotted in a potentiogram (voltage vs time). If the current is sufficiently low and the system is reversible, the voltage may stabilize at a plateau corresponding to a well-defined steady-state redox process. The redox reaction proceeds at a steady rate, determined by the amount of current we allow to flow through the system. The voltage can also deviate from this plateau, and these deviations can indicate what phenomena and to what extent these phenomena take place.

A gradual increase in potential or the so-called overpotential may indicate kinetic limitations or internal resistances due to for example surface film formation. Sudden jumps away from the voltage plateau often reflect mass transport limits. The plateau can in this case shift to that corresponding to irreversible reactions such as gas evolution or electrode degradation.

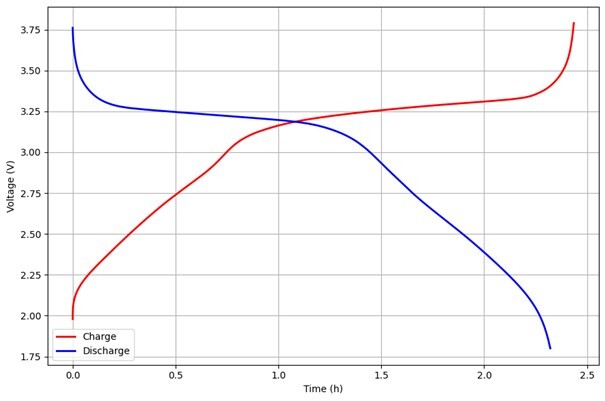

Thus far we have considered a current in a single direction, galvanostatic cycling repeatedly reverses this direction of the current (charging and discharging) in an electrochemical cell. This is one of the most widely used techniques in battery research and performance testing.

Galvanostatic cycling can be done at different current rates which are commonly expressed as a multiple of the expected capacity of the battery or the so-called C-rate. A 1C rate means that the battery can be fully charged or discharged in one hour, a higher C-rate means faster (dis)charging and a lower C-rate means the process is slower. An example, if a battery has a capacity of 100 Ah (ampere-hour) and is discharged at a 1C rate, the discharge current will be 100 A. By measuring the difference in charging and discharging time we can observe the lost capacity, meaning the current was used by a parasitic process. These processes are sometimes desirable, e.g. the formation of the solid electrolyte interphase or SEI, but most often they are not, since they lead to capacity fade over continuous cycling.

The voltage plateaus recorded during cycling indicate where redox reactions occur; for ion-insertion electrodes, these features are typically well defined. Subtle shifts or splitting of these voltage plateaus can reveal structural transitions within the host, such as phase changes or staging phenomena. When coupled with EQCM-D, such features can be correlated to variations in electrode mass and mechanical response, enabling direct observation of how these transitions evolve during operation. Comparing charge and discharge profiles reveals the voltage hysteresis, a signature of kinetic asymmetry and energy loss between insertion and extraction. Increasing hysteresis or rising overpotentials over repeated cycles can signal degradation, loss of active material, or growth of resistive interphases. By tracking the evolution of both the electrochemical response and the accompanying mass and dissipation trends, one can disentangle reversible intercalation from parasitic or resistive processes. This makes EQCM-D a valuable tool not just for identifying when and where ion insertion occurs, but for interpreting how it influences the structural stability and long-term performance of insertion electrodes.

Figure 1: Chronopotentiogram of a Prussian White│hard carbon Na-ion cell (1 M NaPF₆ in EC:DEC).

To investigate such structural changes using EQCM-D, a specialized method known as hydrodynamic spectroscopy was developed. This technique will be discussed in detail in a future blog post.

Chronopotentiometry and galvanostatic cycling coupled to EQCM-D can also be used to observe a wide range of electrochemical processes:

These techniques are especially powerful because they operate under conditions that closely mimic real-world electrochemical applications – unlike sweeping or pulsing methods, galvanostatic testing reflects constant-load performance, as in an operating battery.

Voltage-time techniques like chronopotentiometry and galvanostatic cycling offer a direct and intuitive window into electrochemical systems. By controlling the current and tracking the system’s voltage response, we can probe reaction mechanisms, transport limitations, and long-term performance behaviors with high sensitivity. While simple in principle, these methods remain some of the most versatile and revealing tools in electrochemistry; especially when applied thoughtfully across a range of materials and operating conditions.

Learn more about electrochemistry fundamentals in the webinar Electrochemical QCM-D - a very short introduction. In this session, Viktor covers the basics of key electrochemical measurement techniques, including Cyclic Voltammetry, Galvanostatic cycling, and Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy and how these methods can be combined with Quartz Crystal Microbalance with Dissipation monitoring (QCM-D) to form EQCM-D, offering deeper insights into interfacial processes.

Webinar introducing the energy transition and key electrochemical energy conversion technologies

Wettability plays a crucial role in the efficiency and performance of PEMFCs as it affects how well the FC components manage water.

Wettability plays a pivotal role in Li-ion battery manufacturing, performance, and safety.

The wetting characteristics of the electrode material play a pivotal role in both the manufacturing and performance of batteries.

Read about how EQCM and EQCM-D are used in battery development and help researchers take battery performance to the next level.

Read about how QSense EQCM-D analysis was used to explore the build-up, evolution, and mechanical properties of the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI).

Read about how QSense EQCM-D, Electrochemical Quartz Crystal microbalance with Dissipation monitoring, was used to analyse new battery electrode materials.

Calendering, a common compaction process for Li-ion batteries, will significantly impact the pore structure and thus also the wettability of the electrode.

Viktor Vanoppen, M.Sc., is a guest writer for the blog. When he's not sharing his vast knowledge on electrochemistry and EQCM-D with the blog audience, he spends his time as a PhD candidate at Uppsala University, studying interfacial processes during metal plating for energy storage, combining EQCM-D, automation, machine learning, and advanced modeling techniques like Hydrodynamic Spectroscopy and FreqD-LBM