Superhydrophobic surfaces are extremely water‑repellent surfaces where water droplets form very high contact angles and roll off with only a small tilt. In practice, a surface is usually called superhydrophobic when the static water contact angle is above about 150° and the contact angle hysteresis is below 10°.

In this article, superhydrophobic surfaces are explored from the basic principles and natural examples to practical applications and the key methods used to characterize their performance.

In nature, the lotus effect is one of the most famous examples of superhydrophobic surfaces, where water droplets roll off the leaf and remove dust and particles at the same time. This is a classic example of a self‑cleaning surface.

Under an electron microscope, the lotus leaf surface looks rough and is covered with a wax‑like material. This combination of:

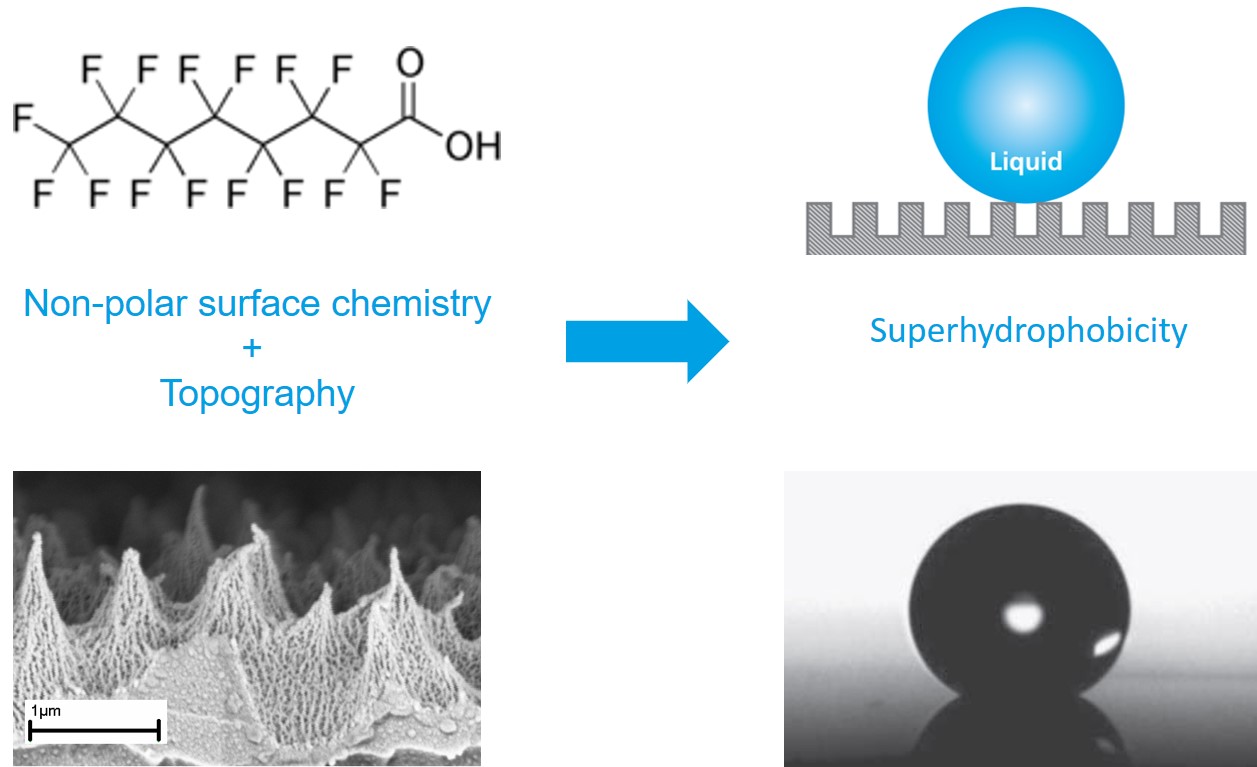

A surface becomes truly superhydrophobic when two things work together: non‑wetting surface chemistry and a micro‑ and/or nanostructured topography.

Non‑wetting chemistry is often introduced through low‑surface‑energy coatings. Teflon® is a typical example of a fluoropolymer with a high contact angle for a smooth surface, around 120°. But this is still below the ~150° water contact angle required for superhydrophobicity, which shows that chemistry alone is not enough; surface roughness is also needed.

In an industrial setting, this usually means:

This combined design allows to reach very high water contact angles and low hysteresis in a repeatable way.

Traditionally, the non‑wetting part of this design has relied heavily on fluoropolymers such as Teflon®. Today, there is a clear push towards more sustainable and PFAS‑free chemistries, so many developers are working on superhydrophobic coatings that combine suitable surface texture with PFAS‑free formulations instead of conventional fluorinated systems.

In microfluidic and life‑science applications, similar design principles are used in wettability‑patterned surfaces for single‑cell trapping, where controlled wettability and contact angle patterns are used to position and hold individual cells.

A hydrophobic surface is one where water beads up instead of spreading out. The term literally means “fear of water,” and describes surfaces that repel water.

Superhydrophobic surfaces go further. They show water contact angles over about 150° and low contact angle hysteresis, which means water droplets slide off the surface very easily. This is what makes them interesting for self‑cleaning, anti‑icing and drag‑reducing applications.

Oleophobic surfaces repel oils and other low‑surface‑tension liquids, not just water. Superoleophobicity is similarly defined as superhydrophobicity but, instead of water drop, an oil drop must form an angle over 150 ° with the solid substrate.

Achieving this is more difficult since oil has a much lower surface tension and oil molecules are not as strongly bound to each other as in water. This requires very low surface free energy and carefully engineered roughness.

In many modern coatings, hydrophobic or superhydrophobic behavior is combined with oleophobic properties to control both water and oils (for example fuels, lubricants or fingerprints) on the same surface.

The strong interest in superhydrophobic surfaces comes from a very broad set of potential applications. Some of the most relevant industrial use cases include:

To properly characterize superhydrophobic surfaces, you need to measure both water repellency (contact angle) and droplet mobility, which is described by contact angle hysteresis and related parameters.

Static contact angle is often the first contact angle parameter to check. A stationary droplet is placed on the surface and its shape is analyzed. For superhydrophobic surfaces, thresholds of static water contact angles above 150° are commonly used.

However, static contact angle alone does not always show which surface has the lowest adhesion to water, so it should not be the only measurement. This is discussed in more detail in our article on contact angle measurements on superhydrophobic surfaces in practice.

Advancing and receding contact angles are routinely measured on superhydrophobic surfaces to calculate contact angle hysteresis.

A common method is the needle method. The drop volume is slowly increased and then decreased, and the advancing and receding angles are determined from the same droplet. The difference between the advancing and receding contact angles is the contact angle hysteresis, which tells you how easily droplets start and continue to move on the surface.

The roll‑off (or sliding) angle is the tilt angle at which a droplet starts to move. It is closely connected to contact angle hysteresis and gives a very intuitive picture of how easily water is actually removed from a tilted surface. The measurement of sliding or roll‑off angle is directly related to contact angle hysteresis.

In summary, characterization of superhydrophobic coatings is typically based on both static and dynamic contact angle measurements, often performed with contact angle goniometers such as those provided by Biolin Scientific. This combination gives a much more reliable picture of performance than static angle alone.

One of the main questions when working with superhydrophobic surfaces is: “How long will the superhydrophobic effect last in my application?”

Even though hydrophobic chemistry is well understood, it remains challenging to produce coatings that tolerate real‑world wear and tear. In practice, the surface may face:

Repeated cleaning or wiping

Abrasion and scratching

Particulate impact (sand, dust)

Washing, chemicals or UV exposure

Often, the static contact angle stays fairly high or decreases only slightly, while the biggest change appears in contact angle hysteresis. When hysteresis increases, droplets do not roll off as before, and the surface has functionally lost its superhydrophobic behavior.

To evaluate durability, many different test methods have been used, including sliding and rotating abrasion, tape tests, and water‑jet exposure. The key is to:

Choose durability tests that mimic real operating conditions

Track both contact angle values and hysteresis before and after testing

Together, these measurements and durability tests give a realistic picture of how long superhydrophobic performance can be maintained under real‑world conditions.

Once the self‑cleaning behavior of the lotus leaf was understood, superhydrophobic surfaces attracted significant interest in the research community. Artificial superhydrophobic surfaces have since been developed across many research groups and relatively quickly found use in self‑cleaning, antifogging and anti‑icing materials and coatings on textiles, among other applications.

Today, if you work with coatings or surface treatments, you are likely asking questions such as:

How can we measure and specify superhydrophobicity in a consistent way?

How do we secure long‑term durability in real life?

How can we combine superhydrophobicity with other functions (for example oleophobicity or anti‑corrosion)?

How do we integrate these coatings into existing manufacturing processes?

As the technology matures, accurate contact angle and dynamic contact angle measurements, together with realistic durability testing, become increasingly important when specifying and comparing coatings.

Superhydrophobic surfaces combine low‑energy surface chemistry with engineered micro‑ and nanostructures to achieve very high water contact angles and low hysteresis. This makes it possible for water droplets to roll off easily, which in turn supports self‑cleaning, anti‑icing, drag‑reducing and other advanced functionalities in industrial applications. With ongoing progress in materials science and surface engineering, new superhydrophobic coatings and applications are expected to be developed in both existing and emerging fields.

Editor's note: This article was originally published December 24th, 2019 and has since been updated for clarity and completeness.

Single-cell trapping can be done with the help of superhydrophobic and superhydrophilic patterns.

Advancing and receding angles should be measured as the low contact angle hysteresis is also a requirement for superhydrophobicity.

There are three contact angle measurement methods for superhydrophobic surfaces; static, advancing/receding and roll-off angle.

A self-cleaning surface is any surface with the ability to readily remove any dirt or bacteria on it. Self-cleaning surfaces can be divided into three different categories; superhydrophilic, photocatalytic and superhydrophobic.

Blood-repellent surfaces are needed in medical devices that come in contact with blood. The traditional approach has been the use of antithrombotic surface treatments However, these coatings are prone to eventually wear-off. Superhydrophobic surfaces have been proposed as an alternative solution.

With increasing understanding of the superhydrophobicity, the measurement methods to quantify the degree of hydrophobicity deserve some thought.

This video will explain two main methods for measuring dynamic contact angle.

Superhydrophobic surfaces were an instant hit in the scientific community when they were introduced over two decades ago

Anna Junnila is Customer Care Manager at Biolin Scientific. She takes pride in making advanced technology accessible for every user and is committed to guiding customers through every stage of their research journey. She holds an MSc in Electronics and Electrical engineering from Aalto University.