One of the key factors to achieve reliable and reproducible QCM measurements is temperature stability. To reach sub-Hz sensitivity, long-term temperature stability at a level of hundredths of a degree is required. In this post we describe which temperature-related artifacts that can arise in the data and explain why temperature stability is so critical in QCM measurements.

It is probably safe to say that the aim of any QCM measurement is to study and evaluate surface interaction phenomena of some sort. The interaction is measured using the resonance frequency -, and preferably also dissipation-, responses, which provide information on mass and structural changes of the surface-adhering layers of interest. However, in addition to the mass and structural changes that are intended to study, there are other factors that also influence the QCM signals. One such major factor is temperature. Insufficient temperature stability during the measurement will, therefore, introduce temperature related artifacts in the data, and in the end, it will not be possible to determine how much of the measured QCM signals that originate from temperature changes and how much that originates from the surface interaction under study.

There are three main sources of temperature induced effects that are commonly observed. A change in temperature will change:

1) inherent sensor resonant frequency

2) viscosity and density of bulk liquid

3) mounting stresses

Due to the properties of quartz, the resonant frequency of QCM crystals is temperature dependent. The specific f vs T relationship varies with the crystal cut. The so-called AT cut, which is standard for most QCMs in surface and interface science-related applications, has a reduced temperature coefficient around room temperature compared to other crystal cuts. However, even for the AT-cut crystal, the temperature dependence of the resonance frequency is still sufficiently large for temperature variations to have a major impact on QCM measurements.

Another, indirect, effect originating in the temperature coefficient of quartz, is changes of the resonance frequency of the reference clock in the electronics. The reference clock is also made of quartz and may be affected at large temperature-variations of the electronics. Should the electronics be exposed to large variations of the temperature, this will directly change the measured frequency. Well-designed electronics employ a so-called oven-controlled crystal oscillator (OCXO) which keeps the reference quartz crystal at a constant temperature (usually well above room temperature) to avoid being influenced by changes in ambient temperature.

QCM technology is sensitive to changes of the bulk solution properties. Both the viscosity and the density of most liquids are temperature dependent, and if these properties change, they will directly affect the measured resonant and dissipation readings.

Mounting stresses of the sensor, induced by for example O-rings and contacts, will always be more or less present. The resonant frequency is influenced by these stresses, and any changes of these stresses will consequently induce changes in f and D. Changes in temperature may for example change both the diameter and elastic properties of the O-rings as well as the dimensions of the measurement chamber (by tiny amounts, but still). Temperature variations may, therefore, result in mounting stress-induced artifacts in the measured responses. For small -temperature variations, this is not likely to happen, and it is therefore considered to be less of a problem than factors 1) and 2). If it does happen however, it is quite severe. And unlike the other two factors, this artifact is not reversible.

Overall, the temperature induced artifacts will manifest themselves differently depending on the nature and origin of the temperature variation. For example, depending on whether the changes are fast or slow, and if they come from the sample or the ambient. Temperature variations induced via the sample may happen for example if you are measuring at room temperature and then use a cold sample directly from the fridge. Essentially, such a temperature change will result in signal spikes. The spikes may be of a large magnitude, but typically they will disappear as the sample temperature equilibrates and returns to the previous value. Variations of the ambient temperature, on the other hand, will generate long-term changes of the signals and result in what is perceived as a drifting baseline. Temperature-induced changes of the mounting stresses can be a result of both sample and ambient temperature variations. They typically manifest themselves as a jump or step-like signal change, which never returns to the previous baseline.

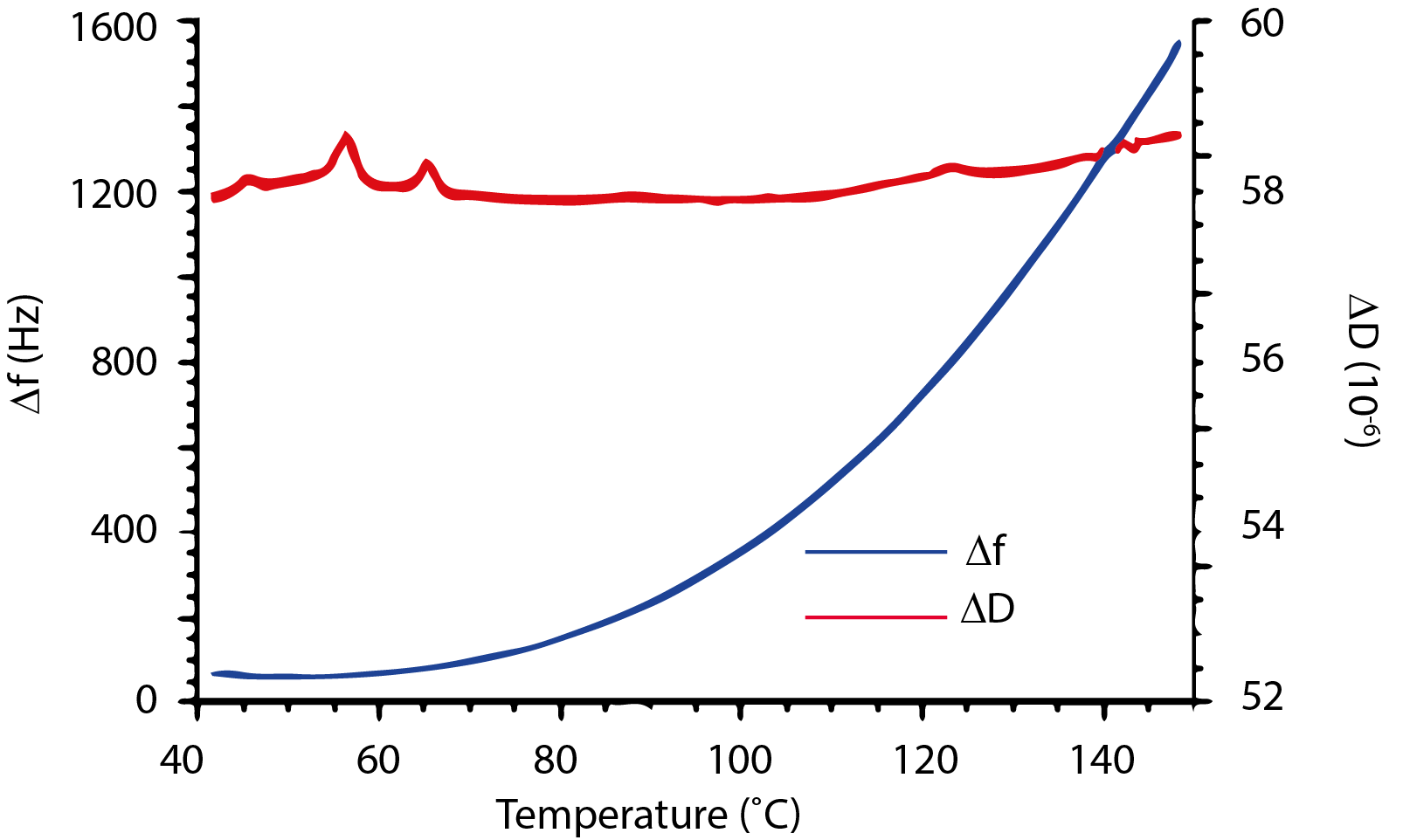

So what distortion magnitudes are we talking about? The extent of the temperature related artifacts depends on several factors, such as if you are measuring in liquid or in air, what liquid you are using, the temperature at which you are running your measurement, and of course the magnitude and duration of the temperature fluctuation. A temperature induced artifact originating in any of the three root causes could be several Hz per degree, Fig. 1. Therefore, to reach reliable measurements with sub-Hz sensitivity, it is necessary to have a long-term temperature stability at a level of hundredths of a degree.

Figure 1. Example of QCM-D frequency and dissipation as a function of measurement temperature. The sensor is coated with a thin polystyrene film, and the measurement is captured in air in the temperature range 40 – 150 °C. In this case, since the bulk fluid is a gas, the main temperature effect comes from the temperature dependence of the sensor’s resonant frequency. The small jumps in the dissipation reading are due to so-called activity dips which is outside the scope of this post.

To achieve reliable and reproducible QCM data, it is essential to ensure a stable measurement temperature. Not only is the QCM resonance frequency temperature dependent due to the properties of quartz, but temperature variations will also induce measurable changes of the bulk properties. In addition, temperature variations may change the mounting stresses of the QCM sensor, which will affect the measured signals in an uncontrolled manner. Depending on the measurement setup and conditions, uncontrolled temperature variations may, therefore, result in one or more artifacts in the measurement data and impede the intended analysis of the system under study. In order to avoid such uncontrolled variations and to reach reliable QCM measurements with sub-Hz sensitivity, the long-term temperature stability needs to be at a level of hundredths of a degree.

Download the overview to learn more why temperature stability is critical and how to avoid temperature related problems.

Editor’s note: This post was originally published in August 2018 and has been updated for comprehensiveness

Compared to QCM, QCM-D measures an additional parameter, and provides more information about the system under study.

Learn about QCM-D, Quartz Crystal Microbalance with Dissipation monitoring - an analytical tool for surface interaction studies at the nanoscale.

Learn about of the acoustic technology, QCM-D, via musical instrument analogies.

Here we explain how Quartz Crystal Microbalance with Dissipation monitoring, QCM-D, works.

Read about how and the QCM fundamental frequency matters in measurements

Read about why it is important for the mass distribution on the QCM sensor to be even, and what the consequences are if it is not.